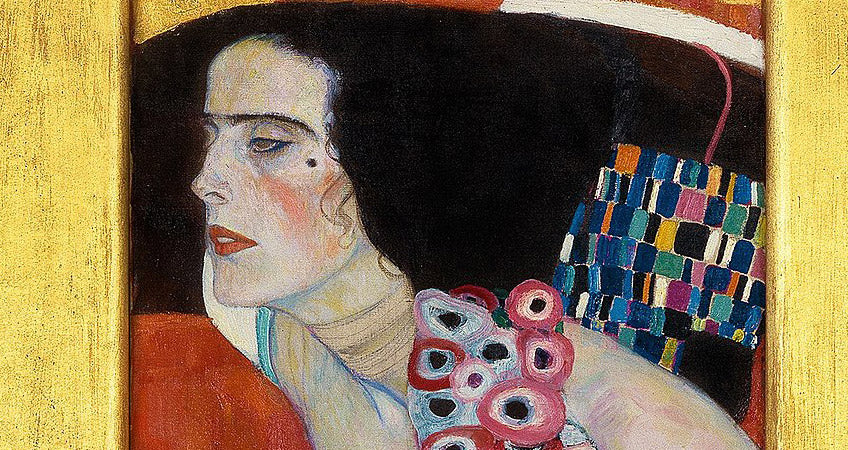

Judith II by Gustav Klimt. Analysis of the work

Matteo CapaldoShare

In 1909, eight years after Gustav Klimt had produced his controversial painting "Judith I", he returned to the same subject. The biblical figure of Judith , who used her charms as a woman to seduce the Assyrian general Holofernes and then beheaded him with her own hands to save the Jewish people with this heroic act. The figure of this courageous woman exerted a particular fascination on Klimt and his contemporaries.

The story of Judith

Judith and Holofernes is one of the most famous stories of the Old Testament. The story takes place during the siege of Bethulia, a Jewish city, by the Assyrian army led by general Holofernes.

Judith was a Jewish widow who lived in the city of Bethulia. When Holofernes and his army arrived in Bethulia, the city prepared for defense. However, the people of Bethulia soon found themselves short of food and water and the situation became desperate.

Judith decided to act and, with God's help, decided to save her city. He dressed in his best clothes and went to Holofernes' camp. Judith was a very attractive woman and Holofernes was struck by her beauty. Judith told Holofernes that she was a refugee who had left the city of Bethulia because its people had rejected her.

Holofernes welcomed Judith kindly and, after entertaining her, allowed her to remain in his camp. Later, Judith hosted a dinner for Holofernes and got him drunk. When Holofernes fell asleep, Judith beheaded him with her own sword.

Judith then took Holofernes' head to her city of Bethulia and showed it to the people. This courageous act inspired the city's defenders to fight even harder against the Assyrian army. Ultimately, Bethulia was saved, and the story of Judith and Holofernes became one of the most famous in the Bible.

For them Giuditta embodied the seductress, a concept of femininity in which eroticism and danger are closely linked. While in "Judith I" Klimt depicted the heroine seen from the front, Judith looking at the observer, in the second version he chose to show Judith from the side.

With his body slightly bent forward, he turns sharply to the left, his eyes fixed on a distant horizon, and his face shown only in profile. By portraying her in such a dynamic pose, Klimt may have established a connection between Judith and another biblical event, namely Salome's Dance of the Seven Veils . Salome, daughter of Herodias, danced for Herod and for her reward, on her mother's advice, asked for the head of the prophet John the Baptist, a wish which Herod granted, albeit reluctantly.

Visually, this sensation of movement is accentuated mainly by the long wavy lines of the two light ribbons that seemingly adorn Judith's magnificent dress.

Klimt also creates a strong sense of eeriness and dynamism with the abundance of embellishments, the very different shapes and contrasting colors in the patterns on Judith's dress and her jewellery.

The elaborate design of the dress consists mainly of geometric shapes , often elongated triangles but also round spiral shapes in different shades of grey. These monochrome shades of gray are enlivened by the bright and different shades of the various floral elements and other decorative elements of the dress.

The richness of intense and contrasting colors culminates in the striking striped pattern on a scarf that is part of Judith's headdress. Equally captivating are the soft floral motifs that cover part of Giuditta's shoulders like a necklace.

Klimt made the background a poorly defined area in fiery red-orange, enriched in parts by golden spiral motifs and the occasional rectangular shape, also in gold.

This orange-red background adds new shades, not used elsewhere, to the already rich color palette that embellishes this painting and further enhances the overall impression of exotic, oriental splendor .

Klimt leads the gaze from the distinctive face of this beautiful woman to her brazenly exposed and erotic breasts, then further down to Judith's hands, with her open fingers clutching the sack from which, at the very bottom of the painting, the decapitated head emerges of Holofernes. In this way, Klimt uses the unusually tall and narrow format of the painting to create an artistic and even dramatic composition in a way that is new to him.

The feeling of dynamism that Klimt generates from the kaleidoscopic colors and accumulation of decorative details also plays an important role in the drama of the image, and this is intensified by the skillful way in which he guides the viewer's gaze.