Are manga art?

Jayde BrowneShare

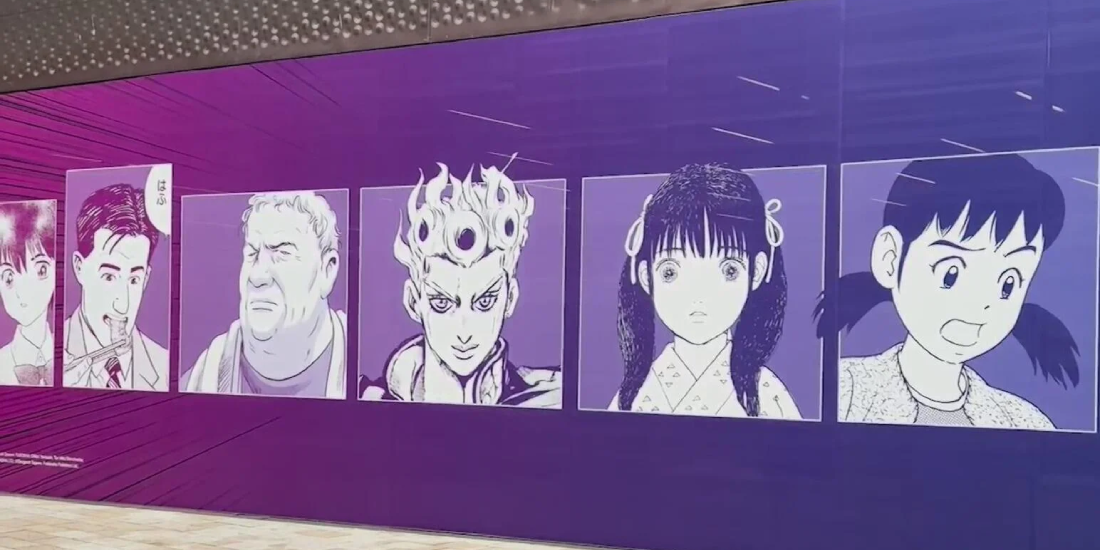

"Are manga art?" A question that, until recently, would have seemed naive or provocative is answered precisely by the title of the largest exhibition ever held in North America: The Art of Manga. Held at the de Young Museum in San Francisco, the exhibition includes over six hundred original works: a parade of panels, sketches, and tools used by the industry's most celebrated artists. Visitors have the opportunity to closely observe the works of eight absolute masters of illustrated storytelling, including names such as Eiichiro Oda, creator of "One Piece," and Mari Yamazaki, author of the innovative "Thermae Romae," renowned worldwide for the quality of their drawings and the depth of their stories.

Manga is more than just entertainment; it is an art form capable of conveying emotion, culture, and profound reflection. The organizers' stated goal is to prove the expressive power of manga, not only to fans but to everyone, highlighting the nuances and details that no digital version could ever fully convey. The original works reveal the artist's handwriting, small corrections, and marks that recount the journey of a scene from the author's mind to the page.

The curator of this incredible exhibition is Nicole Coolidge Rousmaniere, a great admirer of manga culture. Rousmaniere has a personal history of travel and research in the places depicted in manga; the de Young Museum entrusted her with the project after seeing the success of her previous exhibition, held at the British Museum in London in 2019, which had already attracted hundreds of thousands of visitors and brought manga to the forefront of European museums.

Roussmaniere wanted to shine a spotlight on the production process, the labyrinth of choices and efforts behind every page, highlighting the most tangible aspect of creative work, from the first sketch to the final inking. Direct observation of the panels, far removed from the industrial context of publishing, is an experience that changes the way you view comics: from mass-produced to unique works.

The undisputed protagonist of this artistic narrative is Rumiko Takahashi, the queen of hits like "Inuyasha" and "MAO." In her exhibition space, visitors are immersed in the creative process of manga, from the initial draft to the finished work, observing the differences between the various stages and grasping the stylistic choices and technical challenges. This immersive journey reveals the work that goes into each panel, transforming intuition into style.

In the room dedicated to Hirohiko Araki, author of "Jojo's Bizarre Adventure," visitors discover the materials used by artists to bring their unique characters to life. The pens, pencils, and work surfaces testify to a drawing culture deeply rooted in Japan.

But manga also has strong cultural significance beyond Japan: in an interview, artist Mari Yamazaki emphasized how manga is often considered a "mere Japanese subculture," relegated to the shelves of local bookstores, among young enthusiasts, and underground circles. In Europe and the United States, however, we are witnessing a profound reevaluation of this category: manga is studied as an art form, celebrated in museums and analyzed in universities.

This dialogue between manga and Western art institutions opens a fundamental discussion: can manga be fully recognized as a visual art? The hundreds of visitors who crowd the exhibition halls every day seem to loudly answer yes, amazed by the compositional complexity, the literary references, and the power of the images. Many scholars emphasize how manga address universal themes, from personal growth to friendship, from loss to hope, in fantastical and engaging scenarios that speak to the heart and mind.

What emerges from the exhibition is that the definition of "art" is no longer a question of academic prestige, but of emotional and cultural impact.